:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ethanol-plant-d5229326354444ab9e0e79b0b8e05c99.jpg)

On Oct. 20, 2023, an announcement sent shock waves throughout the ethanol industry: Navigator CO2 was canceling the Heartland Greenway carbon pipeline project. Without this pipeline, the ethanol plants it was supposed to connect will have limited ability to sequester carbon, receive tax credits, and be poised to grow.

While the outcome for Navigator's pipeline is clear, the cancellation brought into question what the future looks like for ethanol.

Vital tax credits

Carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) pipelines for the ethanol industry are one of many proposed solutions to eliminate planet-warming carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by trapping the gas below ground for thousands of years. This is to comply with the U.S. government’s long-term strategy to reach net-zero emissions no later than 2050, and keep a 1.5° Celsius limit on global temperature rise.

Pipelines would enable ethanol plants to participate in markets with low-carbon fuel standards, including states such as California and Oregon; or countries such as Brazil and Canada, which plan to gradually decrease their fuel supply’s carbon intensity index (CI). Today’s typical ethanol plant has a CI around 55, and CCS would lower that by at least 30 CI points, according to Monte Shaw, executive director of the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association.

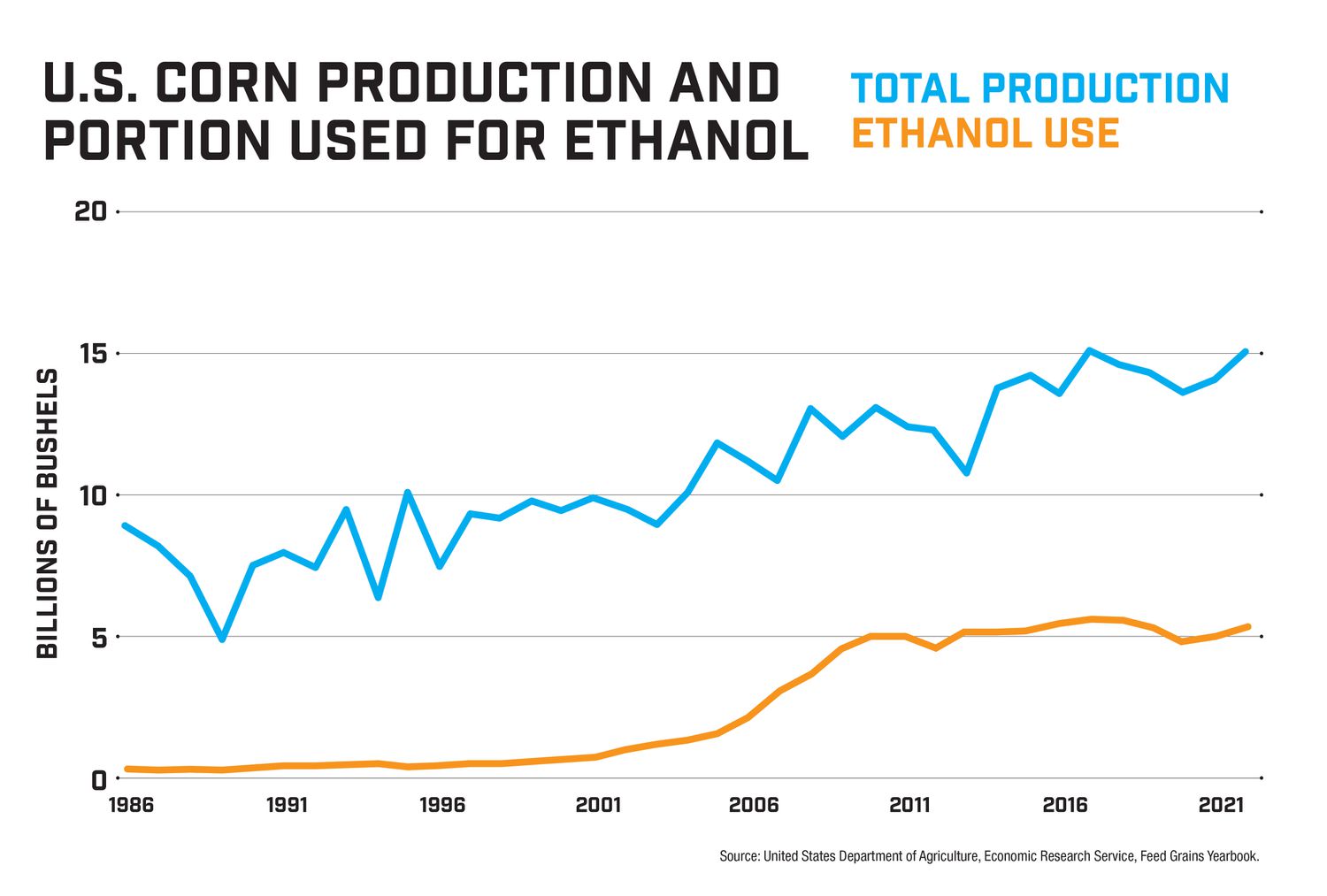

Ethanol production has steadily grown in the United States, with a ramp-up in the 2000s, as nearly all American gasoline transitioned to 10% ethanol. In 1986, of the 8.88 billion bushels of corn produced in the U.S., 290 million bushels — 3% of production — were used for fuel ethanol, according to USDA data. The latest data, from 2022, shows ethanol now accounts for over 5.33 billion bushels: over 35% of U.S. corn production.

Matt Strelecki, USDA

Historically, ethanol has seen bipartisan support in the White House and Congress. During the Trump administration, The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 expanded the 45Q tax credit for CCS introduced under President George W. Bush. This increased 45Q’s credit amount and allowed owners of CCS equipment to claim tax credits.

President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 further expanded 45Q tax credit rates as a means of tackling the climate crisis. Under this law, the Department of the Treasury’s March 2022 tax expenditure estimated 45Q would result in $30.3 billion generated in tax credits from 2022 to 2032.

Shaw cites Trump as the genesis to “every one of these pipeline projects,” but the Biden administration made the tax credits so lucrative, they were necessitated to the ethanol industry.

“If you don't find a way to access the 45Q tax credits, you could lose out on 50 or 60 cents per gallon of ethanol compared to your competitors who do access those tax credits,” Shaw says. “If three neighboring ethanol plants are all getting 60 cents a gallon because they're sequestering their carbon and you're not, the market will move past you. They will expand and survive. You will not.”

The nuts and bolts of carbon capture

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ethanol20plant20by20corn20field2032065097317_994e6d7a39_c-173d59ed11d348f2ad2885e7adfe2692.jpg)

For a simple comparison, Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, former vice president of government and public affairs for Navigator, likens ethanol refineries to breweries. During fermentation, starch breaks down into alcohol, releasing bubbles of CO2. Ethanol refineries release CO2 when they ferment starch from the corn kernel.

The CO2 gas is pressurized, between 1,500 and 2,200 psi, until it’s liquefied. For example, 1,000 gallons of CO2 gas condense to 2.5675 gallons of CO2 liquid. Many plants capture this by-product on their own and store it in on-site tanks.

Dry ice manufacturers use this CO2 to process and preserve food, bottling companies to carbonate beverages, and livestock harvesting facilities to clean and more humanely prepare animals for slaughter. However, this has its limitations as more carbon is produced than these peripheral industries need.

“No matter how hard you try, there’s only so many frozen pizzas,” Shaw says.

Pipelines would move this liquified carbon to a network of wellheads at designated sequestration sites before injecting it into pore spaces around 1 to 2 miles below ground. Pore spaces require a few key traits to make proper underground injection wells. The ground must be porous enough for the CO2 to flow through and be absorbed, and an impermeable layer of caprock must top the porous ground to ensure the CO2 stays sequestered.

Navigating development

Matt Strelecki

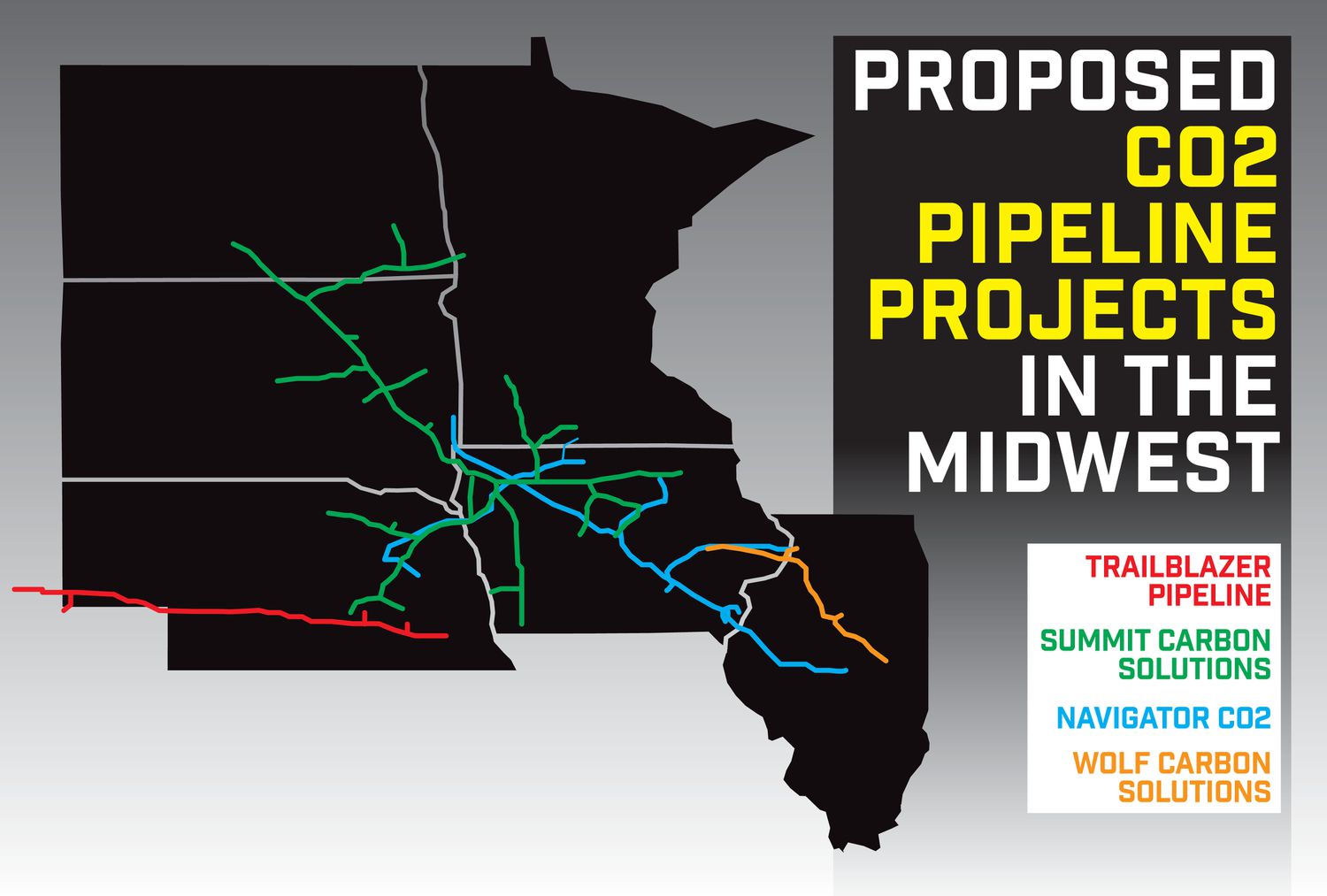

The Navigator CO2 pipeline was one of four major carbon capture and sequestration projects in development in the Midwest, along with Summit Carbon Solutions’ 2,000-mile pipeline, Tallgrass Energy’s 400-mile pipeline, and Wolf Carbon Solution’s 280-mile pipeline.

Navigator’s Heartland Greenway pipeline project began when Valero — an independent fuel refinery and the second-highest producer of corn ethanol in the U.S., at 1.6 billion gallons per year — was interested in building out a broad-scale CCS system that would connect nearly all its 12 ethanol plants in the Midwest. They approached Navigator Energy Services, a midstream service company headquartered in Dallas, Texas.

The project was intended to span the Midwest, passing through Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, South Dakota, and Nebraska. The liquefied CO2 would move in pipelines, ranging from 6 to 16 inches in diameter, to a sequestration facility in south-central Illinois, according to a press release for the partnership’s announcement in 2021.

To qualify as a common carrier for CO2, and to ensure the company wasn’t building the necessary infrastructure for Valero alone, Navigator signed additional partnerships with Poet, Iowa Fertilizer Company, Siouxland Energy, and Big River Resources. Having established partners and an initial pipeline footprint, Navigator held public meetings, and began the survey work and geotechnical analysis to validate the final route for the 1,352-mile pipeline.

Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, Navigator CO2

Around this time, development began on gauging interest in long-term leases of pore space — injection wells — throughout central Illinois. “Think of it similar to mineral rights but almost the complete opposite,” says Burns-Thompson, formerly of Navigator. “As opposed to taking something up out of the ground underneath someone's land, you're putting [carbon] into it.”

All of Navigator’s five footprint states but Nebraska have central permit processes, with their own level of rigor; Illinois has legislation specifically dedicated to CO2 pipeline routing. While trying to adhere to each state’s process, the company began to run into problems.

For most conversations, Navigator negotiated along similar lines of other landowner infrastructure development. If agreeable, landowners would sign easement option agreements and receive 30% to 40% of the easement up front, even if the project fell through — the remainder would be delivered when construction began. To cover yield loss and crop damage during construction, the full easement offered 250% of crop yields for the land, according to Burns-Thompson.

Navigator had rights to execute an easement option on a landowner’s ground within a three-year window, after which the land would revert to the owner. Burns-Thompson describes the easement as not purchasing the land, just the right to cross it.

She says Iowa has the highest level of entry to even begin the conversation with landowners. Before approaching landowners within the state, Navigator had to send a packet of information from the Iowa Utilities Board (IUB) with different chapters of the state code, and a map roughly outlining the project. More details would be provided following a countywide meeting held at least 30 days from the packet’s delivery.

“What is unfortunate about this is the IUB also requires an explanation about the eminent domain process in that letter, too,” Burns-Thompson says. “That doesn't always come across as a positive first impression with landowners.”

Questions about eminent domain took up a lot of the company’s time at county meetings. Burns-Thompson says this clouded Navigator’s ability to have constructive conversations about the project’s finer details.

“From a functional nature and a business perspective, eminent domain doesn’t save Navigator time or money,” she says. “Lawyers are involved, and, frankly, it doesn’t make us any friends. For sheer business practice, [Navigator] was incentivized to do development in a voluntary fashion as much as possible.”

End of the line

Iowa Capital Dispatch/Jared Strong

Navigator CO2 faced multiple major roadblocks in the final weeks leading to its shutdown. In September 2023, the three members of the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission (PUC) rejected the company’s application for a construction permit. Among their reasons were county rules enacting a minimum-distance buffer zone between underground pipelines and homes, schools, and cities. Navigator contended those ordinances were overly restrictive, and sought to have these overruled in June 2023 by emphasizing the pipeline’s safety.

“Navigator’s project poses no serious threat to the environment or the inhabitants where it will be sited,” James E. Moore, attorney for Navigator, said in a brief filed with the South Dakota PUC. “While CO2 pipelines are new to South Dakota, they are not a new type of pipeline, and with respect to their design, construction, and operation, they differ very little from other carbon-steel pipelines transporting hazardous liquids. Because Navigator has appropriately accounted for the toxicity of CO2 in the event of a release through careful plume modeling, conservative routing, rigorous operational controls, and well-planned emergency response, the project will be safe.”

Kristie Fiegen, chair of the South Dakota PUC, said Navigator did not provide timely notices to many landowners intersecting the pipeline’s footprint, nor did it adequately disclose plume modeling, demonstrating what could happen in a potential CO2 leak.

In early October 2023, Navigator withdrew its application for the Illinois portion of the pipeline before the Illinois Commerce Commission and asked Iowa regulators to suspend action there.

“Other developers had reached decisions on permits — most of those were not favorable as well,” Burns-Thompson says. “Our board was looking at whether those were the exception or the rule. Ultimately, the board just did not see a commercially viable pathway under current circumstances.”

Navigator’s final press release cited the “unpredictable nature of the regulatory and government processes involved,” particularly in South Dakota and Iowa.

“As good stewards of capital and responsible managers of people, we have made the difficult decision to cancel the Heartland Greenway project,” Navigator CO2 CEO Matt Vining said in the release. “We are disappointed that we will not be able to provide services to our customers and thank them for their continued support.”

Following the pipeline’s ultimate cancellation, in October 2023, Navigator laid off substantial team members, including Burns-Thompson. The remaining employees are focused largely on continued development on particular parts of the project, specifically what’s been done for CCS injection wells.

“I have been in the agriculture and biofuel space for a bulk of my career, so I've witnessed them have policy and development setbacks before,” Burns-Thompson says. “I believe carbon capture will be a critical next step for the ethanol industry. I think these broad scale-type projects will get built. They may ultimately take different shape and be permitted differently, based on conversation in our nation’s capital about permitting reform.”

Beyond Navigator

Shaw believes there’s room for other pipelines to step up and work with ethanol producers that previously were partnered with Navigator CO2.

“I think the other [pipelines] are moving forward and will ultimately be successful, but we've had a very lengthy process here in Iowa,” he says. “The federal law is clear, the state law is clear: Both say CO2 pipelines qualify as utilities, and eminent domain can be used if necessary, so you're working through the system.”

Summit Carbon Solutions

Jimmy Powell, COO for Summit Carbon Solutions, which works with ethanol plants to capture their carbon emissions, says his business’ sequestration site plan and commercial model separate it from Navigator’s demise. Where Navigator struggled with the EPA to secure sequestration rights in Illinois, Summit has taken advantage of the agency's more lenient regulations in North Dakota to secure a sequestration site in that state.

To protect underground drinking water sources, the EPA has developed Underground Injection Control (UIC) program requirements for each state. North Dakota, Wyoming, and Louisiana are the only three states classified with “primacy,” which makes state-appointed agencies, not the EPA, the primary enforcement authority for UIC well classes. To qualify for primacy, applicant states must meet the EPA’s minimum requirements for UIC programs. Powell says Navigator would have likely needed to change its sequestration site to North Dakota to avoid its difficulties in Illinois.

Powell also pointed to the difference in the two pipelines’ approach to land easements. Where Navigator made partial payments to landowners in the initial easement, with the rest delivered when the project began, Summit makes the full payment up front.

“We have a different group of investors — we're well capitalized,” Powell says. “We've invested a lot of money at this point, we acquired more right of way, and garnered more support in all five states than Navigator had. We feel very comfortable about the future of our project.”

Despite Powell’s optimism, Summit has faced similar challenges to Navigator. The same week Navigator canceled, Summit announced, without explanation, it was delaying its pipeline’s operational timeline from 2024 to 2026. The hearing for Summit’s permit in Minnesota won’t take place until this summer. Summit was denied a permit in North Dakota in August 2023 but was granted a request for reconsideration.

South Dakota is the critical path at this point, Powell says. “We were denied our permit in early September because the PUC didn't exercise what we think is their statutory authority to site the pipeline. They didn't exercise their preemption right, and granted siting authority to some of the counties that had passed ordinances in South Dakota. We've been working with those counties over the last two and a half months to comply with their ordinances, and then we'll reapply early this year.”

In November 2023, Summit concluded its permit hearing in Iowa. A decision is likely in the first quarter of 2024.

In January, Summit announced a partnership with Poet, Navigator’s former partner, to incorporate its 12 ethanol facilities in Iowa and five facilities in South Dakota into the Summit pipeline project. The plants in South Dakota will be included in Summit’s upcoming state application, with separate applications filed for Iowa.

Opponents on all sides

Similar to ethanol’s mixed support in Washington, carbon pipelines have support and opposition from all sides of the political spectrum.

While sequestration isn’t a new technology, environmental groups, such as the Iowa Sierra Club and the Illinois Coalition to Stop CO2 Pipelines, say not enough is known about large-scale CCS long-term effects, and are concerned about the land and water resources required for increasing ethanol production. Those groups say carbon pipelines will prolong the country's dependence on ethanol and prefer that the U.S. invest in alternative environmental efforts such as solar and wind energy, battery storage, conservation, and efficient energy use.

Al Laubenthal row crops, tends 500 head of feeder cattle, and has a custom-feeding swine operation across 3,500 acres of family and leased land in the northeast Iowa community of Whittemore. Laubenthal sells corn for ethanol production and buys back distillers grain for livestock feed. He and his brother no-till 100% of their soybean production, and in recent years have drastically cut back on tillage for corn acres.

“We are doing what we feel is a major step forward in sequestering carbon on our farms,” Laubenthal says.

Summit Carbon Solutions approached Laubenthal with a pipeline offer for 60 rod — just over a third of an acre long — at $1,650 per rod, for a $99,000 total payment. The proposed easement would only cover around two acres but impact 60, running as close as 400 feet to his residence, which gravely concerned him and his wife. Since then, Laubenthal has spent the last year and a half attending meetings and connecting with other affected landowners, concluding this proposal was not good for his farm.

Laubenthal doubts the pipeline’s ability to properly sequester carbon in the earth without also generating more carbon. He’s also wary of the possible burden tax credits would place on the taxpayer. Despite his close relationship with ethanol, he isn’t concerned with the industry’s future, saying other industries would use the corn he grows.

More important to his operation, the pipeline’s construction would disturb soil that has been no-till in some places for as long as 25 years. Around nine years ago, Laubenthal installed drainage tile in parts of his field, which he says still shows signs of disturbance.

“You just don't gain that soil structure back overnight — that takes years to rebuild,” he says.

Tim Burrack farms corn, soybeans, and seed corn on 1,000 acres in Fayette County, Iowa, and implements carbon sequestration practices on his operation such as cover crops, no-till, and strip-till.

Burrack has been selling all his corn to the Poet ethanol facility in Fairbank, Iowa, since it opened 20 years ago. This facility was planned to connect to the Navigator pipeline, and is now planned to connect with Summit's proposed pipeline.

“I lived off government subsidies until the ethanol industry was built 20 years ago, and then we finally had a market for corn: to ethanol, feed, and the export market,” Burrack says. “Once ethanol took off, we had enough demand for corn that we could actually get a decent price for it.”

Before the ethanol plant was built, he hauled his corn to the Mississippi River for international export. But he’s concerned about this market’s viability since Brazil has become the U.S.’s biggest agricultural export competitor. Rather than fight, Burrack says the best recourse is to develop the emerging sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) market. He says ethanol plants and CCS will drastically increase profitability for his operation.

“I see CCS as a way to maintain good prices on corn,” he says. “Others see it as a way to combat climate change — I am not a huge climate change believer. I'm just pragmatic and see the dollars available to agriculture at the very same time we've lost the export business to Brazil.”

Burrack finds Navigator’s cancellation a net positive for the future of CCS, as it allows potential consolidation for miles of overlapping pipeline construction.

Carbon crucible

Following Navigator’s shutdown, Summit’s Jimmy Powell says there’s some trepidation from ethanol plant stakeholders about Summit’s ability to succeed.

A handful of ethanol plants across the Midwest are located on or near sequestration-capable ground — their success is independent from that of the emerging carbon pipeline industry. However, many ethanol plants, like most in Iowa, are not located near suitable sequestration sites, rendering them unable to collect tax credits and compete in the ethanol market.

Iowa Renewable Fuels Association

“This is an industry that has forever lived on a margin you would count in pennies,” Shaw says. “How much would you make on a gallon of ethanol? Five cents? Negative 1 cent? Seven cents for one month? Now, all of a sudden you’re talking about 50 or 60 cents a gallon just from CCS because of the tax credits.”

Powell says Navigator’s shutdown has opened the door for Summit to expand, as it is now the only major pipeline in the upper Midwest, but the future is still uncertain.

“If this project were not successful, it would set back a trillion-dollar industry because regardless of your views on climate change globally and in this country, there's a push to decarbonize,” Powell says. “The future for ethanol plants is low-carbon fuel markets, especially with the emerging SAF market. The only way they're going to be competitive is if they're able to remove the CO2 from their system and it gets sequestered.”

The Inflation Reduction Act introduced tax credits for SAF at $1.75 per gallon, making it the single largest new agricultural market in the world, as airlines and their customers are looking to decarbonize, according to Shaw. A coalition of federal government agencies has posed the “SAF Grand Challenge,” with the goal of meeting 100% of aviation fuel supply with SAF by 2050 — up to 35 billion gallons a year. To qualify, the SAF must have a minimum reduction of 50% in full-life-cycle emissions compared with petroleum jet fuel. That is determined by calculations using the Department of Energy's Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Technologies (GREET) model.

SAF is likely to be produced first from hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA-SAF) — fats, oils, and greases — supporting soybean and livestock producers, with ethanol-to-jet (ETJ-SAF) to follow, according to a study commissioned by the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association. The study projects the market for HEFA-SAF to grow to 3.7 billion gallons by 2050, with ETJ-SAF to grow to 5.59 billion gallons.

To achieve this potential, 63 new 200-million-gallon-per-year ethanol plants will need to be constructed, the study says, along with 30 new ETJ-SAF facilities and six new HEFA-SAF facilities.

The study also found increases in annual corn production are outstripping the growth in non-ethanol corn demand. Without SAF, overproduction would lead to falling prices. In turn, total corn acreage in the U.S. would drop to 68 million acres, resulting in loss of farm income estimated at $259.3 billion. For a typical 1,000-acre farm with 50/50 corn and soybean production, this would mean a drop in revenue of $60,240. With SAF, however, the study predicts corn production will increase to meet ethanol and non-ethanol demand. For the same farm, revenue would increase by $11,760.

Turning ethanol into SAF requires more energy than typical ethanol production, further raising the CI score for refineries producing it. CCS would be the final domino to unlock this market for American agriculture.

“Never before has there been an identifiable market that [farmers] can dominate that’s larger than SAF,” Shaw says. “But if you don’t have CCS, you don’t have the ethanol-powered jet.”

Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, formerly of Navigator, says domestic and foreign marketplaces are going to continue to put a premium on low-carbon products. To stay competitive, rural America needs to lean into new technologies. While Navigator might go away, the drive and the impetus to work with carbon is not, she says.

“I don't think that the ethanol industry is going away,” she says. “We don't get to that future we've been aspiring toward — be that SAF, new waves of bio-based plastics, or the hundreds of other things we can turn corn and soybeans into — without critical investment in infrastructure, science, and technology. We can't be scared of these things.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/_D3_6951-2b36bbe5727444fb9b3b968da4e62f78.jpg)