:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Bring20Soil20Health20to20Life.20Ducks20Unlim2015-2-4dc472d81b3f470bbb4592aeeac92f7a.png)

Running a low- or no-till operation isn't easy. Panelists at the Commodity Classic show in Orlando offered their insights on enhancing soil health by capitalizing on the foundation they've built up in their soil.

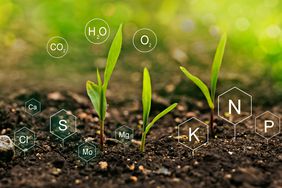

There are six principles to soil health, according to Brian Chatham, an agronomist for Ducks Unlimited, a nonprofit dedicated to the conservation of wetlands.

- Know your context: Chatham says to take stock of your goals and the land you have to work with. It's important to be realistic, knowing that this is a "marathon, not a sprint."

- Maintain biodiversity: Agronomists are looking at more than just a corn and bean rotation. This could mean introducing more cover crops, wheat, flowers, or flax.

- Integrate livestock to the landscape: Prairie soils, for example, are the most biologically diverse soils on the planet, and need to be taken care of both above and below ground, according to Chatham.

- Minimize disturbance: This means reducing tillage and time in the field.

- Maintain living root: Keeping a living plant in the soil for as many days of the year as possible.

- Armor plate the soil: Do what you can to protect the soil, reducing erosion and helping to thermoregulate it. Rain can fall at speeds around 20 mph, shattering the soil structure with each droplet.

Farming with patience

Charles Atkinson is a sixth-generation farmer from Great Bend, Kansas. He began farming in 1980, growing soybeans, wheat, sorghum, corn, hay, and cover crops on over a 1,000 acres of land, in addition to running a cow-calf operation. Atkinson has been no-tilling his land for over 25 years.

"Biggest lesson we've learned is patience," says Atkinson. His farmland started with a clay/loam soil, with "no soil structure." He was told by an extension specialist in his state that he could never run no-till, and took that as a challenge. It took three to four years to build up the soil structure, but once he did, he was able to get into the fields quicker than some of his neighbors.

"Staying true to our crop rotation was important for us," says Atkinson. "Not following the markets, but following what we wanted to do for developing soil health."

Atkinson says there's no one solution to running a no-till operation.

"Nothing is ever perfect," says Atkinson. "I argued with our university when they tried to make a no-till 'cookbook.' You can look at it to get some ideas, but it all comes down to your farm and what you want to do."

Getting started

Chatham says soil testing is an agronomist's "foot in the door" for starting no-till practices. Once that's identified, he will look to see what type of a crop rotation a farmer is currently working with, and whether or not they have livestock.

Once the context is identified, he will begin working to determine the farmer's goals with their operation.

"I work with a lot of producers," says Chatham. "Each cover crop mix we design is different for each producer, and oftentimes in each field is different."

Atkinson's crop rotation mix is often weather-dependent. He starts out with full season beans, will come back in with wheat, and go back into double crop beans, leading to the cover crop in the fall. He may have to run a spring cover crop or run cattle through the pasture sometimes, as well.

Staying nimble

"You have to be able to adapt on the fly — that's knowing your context," says Chatham.

Last year, Atkinson had about 25 inches of rainfall in the spring, and almost no moisture after that, turning his wheat into an unintentional cover crop, resulting in a loss on his fall crops. He typically prefers to bring three to nine species planted across his acres, but this was a year a monoculture just had to work. Even while it's dry, it's important to plant the next crop to keep live roots in the ground.

"In Kansas we always say: We have to kill it nine times before we get a crop," says Atkinson. "We've done a good job, I think we're at five or six right now, so we'll see how the year turns out."

Matt Kruger grew up on a 300 cow dairy farm, and bought an 80 acre farm in Minnesota around the start of the pandemic in 2020. He started growing corn on the land, reducing his tillage in the first year.

Kruger worked with Oatly, an alternative milk company, to see if they could grow food-grade quality oats in southern Minnesota. Weather forced him to no-till plant the oats into corn stock residue, resulting in 101 bushels of oats, which he says was about the same level of yield as the farmers around him working with conventional tillage. After oats, he plants cover crops like sorghum and kale — no-tilled as well. He is still early in his no-till journey, planning to no-till plant corn for the first time later this year.

"Two years ago, I never would have planted oats until an opportunity came," says Kruger. "Hopefully my rotation will be corn, oats, with cover crops in both."

Surviving the transition

Transition to no-till isn't easy, and it isn't always a straight line forward.

"I'll be the first one to tell you, it breaks my heart, but there may be a time in that transition you have to back up a little bit, and put the disc back into the soil to get some of those tracking issues out," says Atkinson.

Farmers may experience a yield drag at first too, but Chatham says "don't burn your house down to heat up a hotdog." This is a long term investment for sustainability — take a look at the big picture before taking drastic action.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/_D3_6951-2b36bbe5727444fb9b3b968da4e62f78.jpg)