:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/DJI_0959-2000-cd9d14a50a344c77878c2083ff21af31.jpg)

Introduced to agriculture in the United States in 1838, the practice of tiling fields has become increasingly important as heavy rain events have occurred more frequently.

The frequency of extreme, single-day precipitation events remained mostly steady between 1910 and the 1980s but has risen substantially since then, with climate change as a major contributor, according to the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. During the entire observed period between 1910 and 2020, the portion of the country experiencing extreme single-day precipitation events has increased at a rate of about half a percentage point per decade. Such weather events often leave fields oversaturated with water.

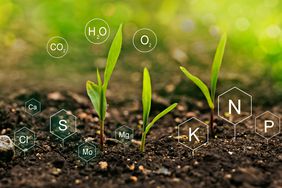

While irrigation practices add water where soil is naturally dry, drainage systems remove from the soil excess water caused by rainfall, floods, or a high water table. Root growth requires about equal amounts of air and water to be present in the soil, meaning desaturation through drainage can create optimal conditions for crops, according to Iowa State University Extension and Outreach.

Drainage tiling has become a bit of a misnomer as the practice has evolved. Tiling was introduced to the United States by Scottish emigrant and farmer John Johnston.

"The first kind of tile was made from clay, similar to terra-cotta roofing tile, and they would hand-lay tile in fields for water to drop into and drain off," says Darla Huff, director of agriculture for Advanced Drainage Systems (ADS). "Over time, they got more sophisticated with all kinds of different shapes of clay tiles."

Marty Sixt and Ronald Martin, who founded ADS in 1966, invented the modern plastic corrugated pipe drainage system. If installed correctly, it is engineered to last up to 100 years, according to Huff.

In modern tiling practices, tile drainage is typically installed at a uniform depth 3 to 4 feet below the soil's surface and spaced across the field 60, 30, or even 15 feet apart. Excess water trickles through the soil into the pipes and is carried off to a designated drainage site, with flow controlled by various gates throughout the system.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/A036-40893-004_ADS_AgInfographics_Illustration-1_Lift_Station_Digital_Desktop-1440x800-1-f50b000f331d43e98fec8316d24a3f72.jpg)

Historically, gates had to be manually opened to release water into drainage sites. Now automated systems allow farmers to monitor and manage their drainage remotely, plus they can set an automated schedule based on the time of year and field conditions.

Once installed, tile drainage takes three years to fully settle into optimal impact for the field, where it can provide up to a 30% increase in yield, says Huff. A 25-year study conducted by Ohio State University found similar results, seeing 30% average increase on corn and soybean yields, taking a 135 bu/acre farm to a 175 bu/acre farm.

Every dollar invested in drainage creates a $1.90 payback when growing corn and at least $1.20 when growing soybeans, on average, according to Michael Maierhofer, market development specialist at ADS.

Field Benefits

Drainage systems can turn previously unproductive fields into profitable land. Chad Henderson farms about 7,000 acres of wheat, beans, and corn in Madison, Alabama, and about a quarter of that land is irrigated.

Until 2021, Henderson had only a few spots of tile across less than 10 acres, but in July of that year, he tiled about 90 acres, mostly with 30-foot centers but decreasing to 15-foot centers in wetter areas. Installation took less than a week, and Henderson was able to immediately plant soybeans on the ground in mid-July, yielding around 15 extra bushels despite the abnormal time of planting.

"After tiling, we were getting 250 to 300 bushels of corn in some areas that we've never grown a crop off of," says Henderson. This boost in yield is spread across small parts of Henderson's fields, divided into spots of tile coverage of 2 to 7 acres each.

In addition to yield benefits, drainage can also help dry fields faster, providing farmers with a larger window to plant and harvest.

Henderson says he could start planting up to a week earlier during the first season after drainage tile installation. He previously would plant the top of the hills, while he waited for lower elevations to dry. With the drainage system installed, fields dry out more uniformly, enabling him to finish planting sooner.

- READ MORE: Soil pH keys soil fertility

Tile drainage can also benefit the environment. Removing excess water can reduce surface erosion. With less water in the ground, soil is also capable of absorbing more applied nutrients, producing less runoff.

"Drainage is a conservation effort; it's managing your water," says Huff. "It's making sure you're using every ounce of water you have on your field in the appropriate way, keeping nutrients in the soil where they belong, instead of running off and going into a stream."

A drainage system will carry off some nutrients as well, but manual or automatic gates can prevent adverse effects such as algal bloom in local water sources. For Henderson, this was an investment worth making for the environmental benefits alone.

"As farmers we're all about efficiency. We're also about trying to make the land better, and [drainage tile] is one of the steps that we can take to do that," says Henderson. "We don't always glean the rewards of the things we do, but maybe the next generation will."

Installation Safety

Installation details depend on specific factors such as water table level, soil texture and class, elevation and slope, and cropping system.

Farmers can opt to work with a contractor or install the drainage system themselves. Jason Brown, president of Mid America Trenchers, says in his experience, farmers with less than 2,000 acres often have more time to handle a project like this, and will install the system themselves and work with their neighbors. He's also seen larger farms buy the necessary equipment, and turn it into a commercial business. Contractors can handle the assessment, planning and construction phases for a tiling project.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/DJI_02722028329-2000-bb59679ba5054731b4d520eebf0e9ffe.jpg)

Henderson worked with a contractor for his installation.

"I've learned over the years that if you're going to do something for the first time, you need to get somebody that does it all the time," says Henderson.

Before starting, contact the local Natural Resources Conservation Service office to get permits. Craig Potts, a member of the Drain Tile Safety Coalition, recommends calling the 811 line in your state to get any utility lines marked and avoid potential disaster during the dig.

Requesting a "Design" ticket from 811 notifies operators of underground utilities near your digging sites and puts out a request for maps and other detailed information to help plan the project.

"It could be real serious hitting a high-pressure pipeline, whether it's gas or liquid," says Potts. "The concern is you could experience equipment damage, or your workers could get killed."

Potts recommends scheduling a meeting between the tile installer and utlities locator to design the tiling plan. The installer should mark planned locations for digging so the locator can best mark where utilities are. Also, installers need to consult with state zoning requirements to determine the minimum clearance on either side of the pipes.

Farmers who install tiling regularly start at either 30- or 60-foot centers and expand from there depending on in-field results.

"I don't know any farmer that has ever installed a tile system and regretted it," says Huff. "I joke that it's like a tattoo. You can't do it just once — usually if you get one, you get two. Everybody does it more than once."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/_D3_6951-2b36bbe5727444fb9b3b968da4e62f78.jpg)