:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/51221116749_2c6e899c6e_o-2000-6068c7f93cb4480e8c545f5e5f3e3739.jpg)

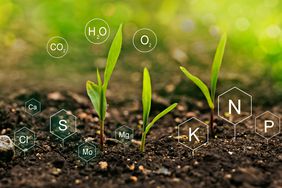

Farming practices have evolved since farmers first tilled the soil, with expectations of greater yields occurring each year. Yet, one element remains unchanged — the importance of soil pH.

- READ MORE: Allow the soil to work for you

"When it comes to soil fertility management, soil pH is the first thing I look at on a soil test," says Tryston Beyrer, crop nutrition lead for Mosaic. "Our greater adoption of reduced tillage, no-till, and sustainable production practices affects how soil pH is managed in our crops.

"When farmers first broke ground, there was natural fertility," he adds. "Now we look at what we need to do to maintain that fertility or balance nutrients so they can continually be released for plant uptake. Soil pH level is one fundamental that must be determined."

Soil pH is the degree of soil acidity or alkalinity in a soil. A pH of 7.0 is neutral. Below 7.0 is acidic; above it is alkaline.

"Our goal is to be between 6.0 and 7.0 on the pH scale, which is usually the prime areas for release of all the other nutrients," says Noah Goza, soil fertility specialist with Heartland Soil Services.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Screen20Shot202022-08-2620at202.42.4620PM-2-c0a5370e7bf84cf0bd969cccb51cee97.png)

Alfalfa needs pH at about 6.7 to 7 and sugar beets a little higher, says Beyrer. A 1-unit drop in pH could decrease nutrient availability by 25% to 30% and decrease plant health and yield. For example, fertilizer efficiency is 80% in soil with a pH of 6. It drops to 46% at 5 pH. (See soil pH-fertilizer efficiency chart, above.)

How Farming Practices Impact Soil pH

Soil pH maintenance allows crops to better use soil nutrients. The latest soil test summary from The Fertilizer Institute shows decreases in soil pH nationwide, likely because of high crop yields and modern production practices that place heavy demands on soils.

For example, Beyrer says low-till and no-till systems typically aren't incorporating commercial fertilizers into soil as deeply as conventional tillage achieves. The upper couple of inches of soil in these fields become more acidified at a lower pH than subsoil.

"Aside from limiting nutrient availability, low pH in the upper part of the soil can affect herbicide efficacy," Beyrer says. "Plant growth is less robust due to aluminum toxicity, more phosphorus tie-up, and less microbial activity."

Practices to Help Manage Soil pH in No-till

Tillage. Tilling as little as once every 10 years mixes acidic topsoil with alkaline subsoil.

Prescriptive tillage. This practice tills just one part of a field one year and another the next and so on until mixing is completed.

Lime. Repeated applications of lower rates of a higher-efficacy lime help manage surface soil acidity.

Banding. Applying nutrients deeper into root zones limits soil fixation.

Changes Take Time

Be proactive for changing soil pH, Beyrer says.

"For corn and soybeans, you want pH in the 6.3 to 6.5 range," he says. "If lower, consider applying lime throughout the soil profile. If higher, give it time to decrease through natural root acidification and fertilizer use."

Soil chemistry can take two months to several years to neutralize soils, depending on the lime source, soil parent material, and soil texture/buffering capacity. Proactively measuring and making small changes to soil pH support soil microbiology, nutrient availability, and plant growth, compared to making significant changes less often. Reevaluate soil pH levels every two to four years to ensure they're stabilizing at desired levels.

"There are no silver bullets," Beyrer adds. "We must make the ground under us work harder than we ever imagined. Maintaining proper soil pH takes more than one tactic."