:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/monitor-2-2000-58deae0865b047708edb80e58a5e6291.jpg)

Dr. Jason scowled as he listened to the rumbles coming from deep in my lungs.

"You know you aren't going home, right?" he asked. "Because you've failed at caring for yourself at home."

- READ MORE: It's just a cold

This news wasn't surprising. I had visited the ER a few days earlier and was diagnosed with human metapneumovirus along with a possible pulmonary bacterial infection. Things didn't look too bad, so I was sent home with oral antibiotics.

After my condition steadily worsened I reported back to emergency room. The medical staff immediately put me on oxygen and installed an IV port in my arm. The port had soon handled a good deal of freight, including enough steroids to turn me into the Incredible Hulk, and enough antibiotics to treat a truckload of cattle with shipping fever.

Lurking in the background was my past experience with hydrogen sulfide.

In 1988, I entered a manure pit on our family dairy farm and was overcome by the noxious gas. I spent more than a month in the hospital, including three weeks on a ventilator.

Were there scars in my lungs that the bacteria was using as a party pad? Would this make it more difficult to evict the malicious microscopic miscreants?

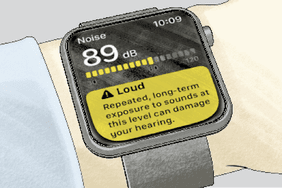

I was installed in a hospital room where the window afforded a sweeping vista of the adjoining rooftop. Electrodes were glued to my chest and wired to a device that continuously displayed blood oxygen levels and cardiac activity.

The simple act of using the bathroom was a logistical nightmare. I had to gather all the wires and tubes before I could even get out of bed. I had to plan ahead to use the loo.

Numerous medical professionals soon visited me. Chief among them were respiratory therapists who administered nebulizer treatments. A nebulizer treatment involves donning a mask that covers the mouth and nose. A stream of oxygen causes a liquid medication to turn to a steam that's inhaled. It's like vaping except that it's good for you.

They tested me for COVID-19 three times; each was negative. I had all of COVID-19 symptoms, just not the actual disease.

Worried looks began to appear on the faces of my caregivers during my second day in the hospital. I was told that my standard oxygen cannula needed to be swapped out for a high-flow model.

A high-flow oxygen cannula is essentially a miniature clothes dryer vent tube that delivers a turbocharged blast of heated, moisturized oxygen to the nostrils. I thought that being given a high-flow cannula simply meant that I was getting an upgrade due to my status as a valued customer.

Not so.

Had I continued to worsen, the next step would have been a return engagement with the dreaded ventilator.

Word got around regarding my manure pit accident. Some of the medical staff mentioned it during their visits, incredulous that I was still walking around and that I hadn't spent a nanosecond in the hospital or needed supplemental oxygen over the past 34 years.

As a veteran of respiratory distress, I knew how to play the game with respiratory therapists. You do everything that they tell you to do – and then do more if you can.

I was given a respiratory exercise doohickey nicknamed "the pickle," owing to its cucumber-like size and shape. When you blow into the thing, it magically creates vibrations that can be felt deep in the chest. I wanted to take the pickle apart to see how it worked but thought better it.

Thanks to the internet, you can view your medical records anytime you want. I signed onto my patient portal with my laptop to see what was being charted about me.

The words "admitted with acute hypoxic respiratory failure" leapt off the page. I hate being labeled a failure in any context. On the other hand, it was clear that I wasn't being a wimp or faking it.

My symptoms slowly improved over the course the next few days. I was weaned off the high-flow cannula and the number of intravenous antibiotics were reduced to just one. I obsessed over my blood oxygen levels and blew into the pickle as I paced around my hospital room.

After five days that each seemed like a year, I was finally cleared to go home. Dr. Jason dropped by my hospital room shortly before I left.

"You were pretty sick for a while there," he said, wearing an expression that seemed to say, We saved this one!

"I guess so," I replied. "Don't take this the wrong way, but I hope to never see you again."

"That's fine by me," he replied with a grin before disappearing down the hallway like a scrubs-clad phantom.

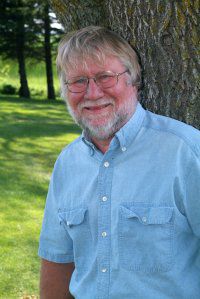

About the Author

Jerry Nelson and his wife, Julie, live in Volga, South Dakota, on the farm that Jerry's great-grandfather homesteaded in the 1880s. Daily life on that farm provided fodder for a long-running weekly newspaper column, "Dear County Agent Guy," which become a book of the same name. Dear County Agent Guy is available at workman.com/products/dear-county-agent-guy.