:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/current_al_none-a5321421d65d470b994502fb4fde4f16.png)

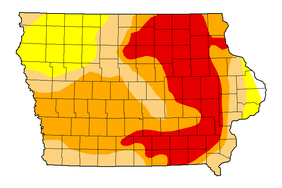

U.S. Drought Monitor

A rainless autumn has caused drought conditions to intensify in Alabama, resulting in more input costs and rising concerns about pasture damage for livestock producers.

Clay Kennamer, a stocker operator and cow/calf producer in Hollywood, Alabama, says, while he doesn’t plan to cull any cattle beyond his normal amount, he anticipates spending a significant amount of money to keep his cattle fed this winter.

Normally, Kennamer says that he’s able to graze throughout some of the winter months on a limited basis—two hours at a time. This year, though, Kennamer says he won’t have that option. This is because Kennamer wasn’t able to get oats planted until late, and little to no rain has allowed the oats to grow to a grazable level. “Normally I would have been grazing the cattle already,” Kennamer says.

Kennamer says that the oats and rye grass that he planted for winter forage won’t begin to help him from buying additional feed for his cattle until March at the earliest. He says he can’t even find the rows where it was planted.

The forage isn’t dead, though, Kennamer says. A lack of warm weather and daylight paired with a late planting is keeping it from growing, he says. “If we could get a week of 60s during the day and 40s at night, we could actually grow something,” Kennamer says.

The latest drought monitor map for Alabama shows that 17% of the state is in D3 extreme drought. Thirty-one percent of the state’s acres are in D2 severe drought, 19% is in D1 moderate drought, and 22% is abnormally dry. Just 11% of the state is free of drought stress.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/IMG_0913-fd3c292a081945d8a4589f1c934ff252.jpg)

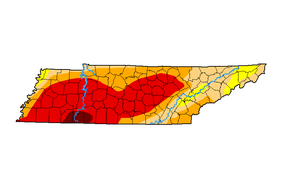

U.S. Drought Monitor

Matt Webb, an extension agent in Jackson County, Alabama, and a sheep producer, says that some rains from the past three weeks have helped grasses to germinate, but says those won’t help livestock producers until later in the spring.

Webb says that the cattle producers that he works closely with all began feeding hay at the end of September, which is four to six weeks sooner than normal. As a result, Webb says that it will be a challenge for producers to stretch their hay through the winter months. He says he’s already gotten calls from cattle producers about how to supplement the feed to stretch their hay supplies.

Right now, Webb says that pasture quality is really low and has been low since October. Luckily, Webb says a good growing season allowed hay farmers to get two to three cuttings of hay to help feed the cattle through the winter months.

What Webb is really concerned about, though, due to the drought conditions is how much pasture damage that will take place over the winter. “I’m afraid we’re going to see a lot of pastures overgrazed,” he says.

Webb is already anticipating phone calls in the spring from producers asking how to repair their damaged pastures. In an effort to prevent too much damage to the pastures this winter, Webb says if producers can move their livestock to an area that they don’t mind sacrificing, “either close to the feed source or a field with fertility problems,” then the costs of renovating those areas will be smaller.

Other advice Webb has for producers to protect their pastures is to keep the livestock off of them until the grass is able to get about six to eight inches tall. “Shut the gates,” Webb says, “and whatever grass is out there, give it a break.”