:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/29860Scouting-78238653706d4d7aaaa4ef52a1d8f495.jpg)

On the surface, scouting seems simple. Getting into the fields on a regular basis to understand weed, disease, and pest pressure is a farmer’s first defense against problems in the field. But for many, finding time to scout fields and analyze findings can be a delicate balancing act with other priorities.

“Scouting is so critical to be done timely and often,” says Eric Andersen, who farms outside of Dike, Iowa. “We make plans on inputs and applications all winter long, but the weather, environmental conditions, and soil conditions can vary so much from year to year and from field to field. It is really important to have boots on the ground and be out there assessing if those plans really are the right decision.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/FarmSchooliconredtassel1-884b03b504ba4a74bff7d30e3346b098.png)

An educational series for farmers who want to take their skills to the next level. Check out more Farm School content HERE.

Scouting 101: Start Simple

Ideally, scouting begins as soon as plants emerge and continues on a weekly basis throughout the growing season.

The first trip into the fields allows farmers to gather data on the success of their planting process. Take note of emergence rates, moisture, and early weeds when scouting in the spring.

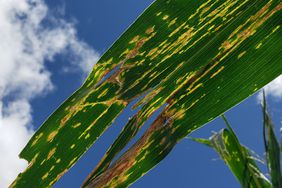

“It’s mainly about environmental conditions and weed conditions in the early part of the season,” Andersen says. “As we get farther into the season, it becomes more about diseases and insect pressure.”

Rather than checking just one row or area of the field, implementing a specific walking pattern through the field can provide a holistic view of field conditions. Summer Ory, who farms in Earlham, Iowa, with her husband, Dan, uses a zigzag pattern when scouting.

“You don’t just evaluate one plant and then prescribe a spray treatment for the whole field,” Ory says. “You need to go out and zigzag your way down the rows and take several points of contact. Then move to another side of the field and do it again so that you’re getting a region of acres that you can comfortably say whether the field is ready for a treatment application or not.”

Checking areas with different conditions is also important in understanding the field’s health. Low areas, sidehills, hill-tops, and field edges could all face different pressures.

“I like to take an ATV out into the field to cover a lot more acres than I could just walking through,” Andersen says. “I also know the past history of these fields, so I know what I need to watch out for in specific areas.”

Scouting can also provide an opportunity to gather in-depth data through tissue sampling, soil sampling, and root digging. Combining this data with that gathered visually can lead to better mid-season management decisions.

Once a problem has been identified, evaluating the size of that problem can help guide decision-making.

“We take how much a field is affected into consideration,” Ory says. “If just one or two plants are affected, it may not warrant treatment at all. We just need to keep an eye on it in case it magnifies. In some cases, you come back a week later and all of a sudden you have a problem that you need to deal with. If it is some-thing that is only going to get worse, you have to deal with it right then and there, so that there is a better opportunity for high yields come fall.”

Scouting 201: Stay Informed

Several components can change the focus of a scouting session. Weather patterns can exacerbate certain problems, and certain pests, diseases, and weeds can all spread from neighboring fields.

Staying informed about what’s going on beyond the property line can help farmers focus their efforts on the issues most likely to pop up.

“A cool, wet summer would definitely bring on a higher likelihood of certain pests and fungal diseases, whereas a hot dry sum-mer would bring on a whole different ball game of pests and diseases,” Ory says. “We would react a little bit differently to both of those, so it’s important to get out and check the crops so we can make a judgment call.”

Building upon knowledge gathered in past years is also essential to knowing what to focus on.

Ory uses data management software to compile notes and observations throughout the year. She notes everything from which varieties are planted in each field to what weather conditions she faced.

“Every year we build on things we’ve learned in the past, but then we also kind of break ground into new topics,” Ory says. “That helps me become a more well-rounded agronomist. I don’t know that we would come up with this information on our own if we were just out walking around with no guidance. Studying those things helps us stay focused and creates a big picture of why a crop performed the way it did.”

Scouting 301: Use Trusted Advisers

Whether it’s getting advice from local Extension or hiring scouters in the busier seasons, trusted professionals can have a major impact on the success of scouting.

Ory on each scouting trip carries a laminated notebook filled with notes from advisers.

“Both Extension and our agronomists are a very valuable resource,” Ory says. “They made field notebooks that we take out with us and reference. Sometimes you see some-thing with identifiers that are not quite what you’re used to seeing. It’s good to have those notebooks to reference.”

Hyperlocal advisers can have intimate knowledge of specific fields and the problems they may face. Andersen hires workers from the local co-op to scout his fields throughout the summer.

“I use several different sources for information including a scouting firm and two agronomy suppliers,” Andersen says. “Extension is a good resource, but they cover more of a general area while my agronomists are more specific to my area.”

Having local experts can allow them to gain familiarity with each field year after year.

“My agronomists know my fields, so they know where problems come up,” Andersen says. “They also relay to me what helped the neighbor across the fence or down the road.”

Andersen utilizes his agronomy team to get multiple eyes on his fields. The extra assistance also allows scouting to be prioritized when other farm chores call.

“There’s a lot of have-to-do things that need to get done in a day,” Andersen says. “Crop scouting is one of those have-to things. It’s a matter of trying to fit it in during the day because it’s important to get across to all those fields in a timely manner.”

With a wide array of pests, diseases, and weeds to be on the lookout for, scouting can quickly become overwhelming to a new farmer. Ory recommends finding a mentor that can guide the process.

“You’re looking at a lot of information and trying to diagnose a field and make a judgment call,” Ory says. “A mentor can guide you through those early years to give you a good base to move forward. A lot of things can happen in season. What happens between planting and harvest is where there’s a lot of opportunity, but there’s also the potential for a lot of failure.”

Check out more Farm School content HERE.

This educational editorial series is sponsored by:

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Cortevanewsize0823-2-502f2cd1d6824210adc734382955ec33.jpeg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/headshot-bc4ff3c0c50c4e1cb8156ba02e8bf428.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/29860ScoutingR5A_1614-014-0fec417490ec40aabdf79b657b746442.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/29860Scouting-R5A_1560-007-8cb4505af96c45c6b052db88b225dd7a.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Scouting-R5A_1780-035-f8c8ca5b7189428785a5279b116134ce.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Scouting-R5A_1660-017-297c068ad75549db9810f6b969ca80f2.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Scouting-R5A_2126-097-2968616302ae4ea289f54d3678def378.jpg)