:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/2916820Winter20wheat20root202021-2-2000-2196506ec323428bb829d8e940253890.jpg)

Preserving his farm's population of beneficial insects is a critical management goal for Bryan Jorgensen, an agronomist for his family's operation, Jorgensen Land and Cattle near Ideal, South Dakota.

"Insects are a primary part of the biome; it wouldn't function without insects," he says. "Their activity contributes to the building of soil organic matter, for instance. Beneficial predatory insects eat pest insects. Some insects are pollinators. Others are herbivores that regulate weed populations by eating weed seeds."

- READ MORE: Pollination goes high-tech

The combined activity of beneficial insects, he says, contributes to the overall profitability of the farm. The economic benefits spin from multiple services performed by helpful insects. Pollination of flowering crops by insects boosts yields, for instance. The predation of some beneficial insects on crop pests may reduce the need for insecticides and fungicides.

Evaluating the extent of the beneficial insect populations in the fields and whether these populations continue to grow is an uncertain science. One yardstick Jorgensen uses to evaluate the activity of insects is the soil itself and its ability to absorb moisture.

"I watch how the soil reacts to water infiltration," he says. "Insects create macropores and micropores in the soil, and these facilitate rapid water infiltration."

While it's not a yardstick of existing insect populations, Jorgensen says simply leaving residue on the surface of the soil is key to building populations of insects.

"If you have a healthy soil system — with residue on the surface — you're going to have tons of insects, and if you look beneath the residue, you'll see them," he says.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/2916820Bryan20Jorgensen-2-9e60ab4b534549fd8a604cf71dacf0ab.jpg)

Jorgensen remembers a time when his family's farming system was an unhealthy one. "I started farming in the mid-1980s, and at the time we used lots of tillage," he says. "We had summer fallow, and we kept it tilled black. There was little opportunity for insects to thrive, and certainly the tillage prevented any chance for insects to build micropores and macropores in the soil."

Five Soil Health Principles

Over time, the Jorgensens developed their present farming system that incorporates no-till, diverse crop rotations including cover crops, and livestock grazing.

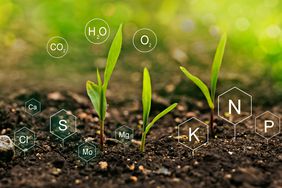

"We practice the five principles of soil health, which are all important to maintaining a healthy soil system, including a healthy population of insects," says Jorgensen. "We keep the soil surface covered with residue. We disturb the soil as little as possible, and we try to keep living roots in the soil for as long as possible. Living roots create a host environment for a living biology.

"We also try to mimic nature by growing a diverse population of crops, and we integrate livestock grazing into the system," he says. "Through their manure and urine, grazing cattle, sheep, or goats spread nutrients from the crop residues back onto the soil surface. The insects then move these nutrients back into the soil system."

The diverse crops the Jorgensens grow include winter wheat, corn, grain sorghum, soybeans, oats, spring wheat, field peas, alfalfa, forage sorghums, and tame grasses.

"On some of our poorer ground we establish tame grasses for 10 to 15 years to build soil health," says Jorgensen. Most of the crops are fed to their livestock.

They grow a multispecies cover crop behind winter wheat. "We harvest the wheat in mid-July, and behind that we plant a cover crop mix including eight to 12 species of both warm-season and cool-season plants," he says. "We graze cattle on the cover crops in November, December, and January."

With the grazing of the cover crops and the mechanical harvesting of crops, they keep a close eye on the amount of residue that's being removed from fields. "We have to replace that residue with some other kind of residue or nutrient, otherwise the system will go backward and organic matter will decline," says Jorgensen.

Because soybeans, for instance, typically leave little residue on the soil surface after harvest, the Jorgensen farm tries to plant winter wheat, a high-residue crop, after the soybeans if weather and moisture permit.

"If we don't plant winter wheat behind the soybeans, we'll plant oats or spring wheat on that field in the spring," he says.

The most effective way they have found to maintain surface residue and build soil organic matter is to graze cattle on cover crops. "Across the farm in 2021, the average organicmatter content of our soil was 4.3%," he says. "Some fields tested as high as 8.5%. Those were fields that had a history of very little removal of crop residue and a lot of cattle activity," he says.

Before adopting their regenerative management system, the organic matter in their soil typically ran about 1%.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/2916820Carabid20beetle-2-364a642232c24d7c8cb504ca2fbbd408.jpg)

Carabid beetles are powerful predators of harmful insects.

| Creating Habitat for Insects |

|---|

| Jonathan Lundgren has devoted his life to studying insects and their role in agricultural production systems. After working as a research entomologist for the USDA-Agricultural Research Service, he founded Blue Dasher Farm, Estelline, South Dakota, as a research and demonstration farm in regenerative agriculture. |

Most Insects Benefit Farmers

Regenerative management practices have increased beneficial insects that help maintain healthy crops and a healthy soil system. Jorgensen does everything he can to protect their well-being.

"I don't use any insecticides, with the exception of controlling alfalfa weevils every five or six years," he says. "I also use no fungicides. In a healthy system, plants can typically defend themselves against viral infections.

"Unfortunately, many of us have been taught that insects are bad, and we have to spray them," says Jorgensen. "In truth, most insects are beneficial. It's only a handful that cause problems. Healthy soil and cropping systems need insects to thrive."