:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/illinois-irrigation-water-issues-9c3fbc17855c4227bce4df89c47cfe23.jpg)

While Illinois is not currently facing a water crisis, highly populated areas with high growth – namely Chicagoland and Champaign County – are undergoing some levels of water conflict, partly because of agricultural irrigation.

The State Water Survey projects that in the coming decades, Illinois will require 20% to 50% more water. But planning for the increase has been inadequate, largely due to a halt in planning because of the ongoing state budget crisis, government water experts say.

In 2006, then-Governor Rod Blagojevich issued an executive order that the water survey and Illinois Department of Natural Resources would develop state and regional water supply plans for 10 regions of the state.

However, only three of those plans were completed, and two were being developed when the Illinois Department of Natural Resources suspended all regional water supply planning activities in March 2015 because of a lack of funding from the state legislature. Five plans were never started.

Wes Cattoor, who oversees water-supply planning for the department, said the plans were prioritized by which areas were most likely to see water conflicts – with Chicagoland (where there is already conflict), east central Illinois (where there is irrigation and high population areas), and the Kaskaskia River Basin (where irrigation is heaviest) being completed first.

Even though these plans were completed, their implementation stopped with the funding.

Nora Beck, a senior planner for the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, said the report helped the agency create its GO TO 2040 report, a plan intended to help the Chicago metropolitan area preserve its quality in the future.

Beck also said the planning agency used the information to help municipalities with technical water-supply issues and showed many communities they are losing a great deal of water through their distribution networks.

CMAP would like to be doing more, she said.

"We really want to do water-supply planning," Beck said. "There are some efforts under way, but they might not be as rigorous as we like."

Illinois is limited in the amount of water it can take out of Lake Michigan to 3,200 cubic feet per second, or 2.1 billion gallons a day. Illinois has remained below that threshold in recent years, but conflicts have had some communities looking back at Lake Michigan as a potential source.

Consider:

- Between 2005 and 2015, Chicago more than tripled the price it charges to more than 100 suburban communities that purchase water from the city, which had communities looking for different solutions.

- In the suburbs of Chicago, communities like Elgin and Aurora use a combination of well water and water from the Fox River. In summer 2016, they had to rely more heavily on well water because of an algae outbreak on the Fox River that made the water taste bad.

- Joliet gets its water from a deep sandstone aquifer but could see shortages as soon as 15 years from now.

- The city of Geneva invested $24 million in a reverse osmosis water treatment plant in 2008 to treat deep and shallow well water.

- Municipalities in Lake County are spending about $250 million to get water from Lake Michigan after issues with well capacity and contamination.

- McHenry County, which has both irrigation and a large suburban population, is too far away from Lake Michigan, and the water survey has projected groundwater shortages that could affect rivers and streams as soon as 2050.

"There has been more water use from aquifers that aren't going to be able to support (additional growth) down the road," said Steve Wilson, a groundwater hydrologist at the Illinois State Water Survey, who made it clear that this has not yet happened. "You can only use so much groundwater without dewatering an aquifer."

These conflicts are important because they could drive water use law in Illinois – with unintended consequences for irrigation.

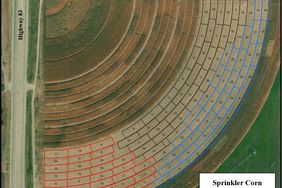

There is currently very little water law in Illinois. The reporting of irrigation wasn't required until 2015, no one regulates whether irrigation pivots can be installed, and there are no restrictions on groundwater usage.

However, because of conflicts in the Chicago area, some legislators have looked into restrictions on high-capacity water use, though no action has been proposed, said George Roadcap, a groundwater hydrologist at the Illinois State Water Survey who serves on advisory boards in northeastern Illinois.

"Some of it makes good sense; some of it doesn't," Roadcap said. "Some downstaters are worried that some legislation is going to get passed that is driven by something in Chicago that makes no sense for downstate."

Wilson said he tells irrigators that they need to report so the Water Survey can have the best data to work with to make future decisions.

"What I keep telling irrigators is that we need to be concerned about providing good data and having good information, because eventually there is probably going to be water law in Illinois, and it's probably going to be driven by the Chicago area, and it will probably impact downstate," he said.

Cattoor said the lack of funding makes it harder to answer questions about future groundwater availability.

"That's what we're trying to find out," Cattoor said. "Will there be issues in the near future?"

He said if the state has knowledge about groundwater, issues are much less likely.

"That's why water-supply planning is so important. We have those tools to find out where the problems are," he said.

By Johnathan Hettinger, Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting is an independent, nonprofit newsroom devoted to coverage of agribusiness and related topics such as government programs, environment and energy. Visit us at www.investigatemidwest.org or follow on Twitter @iMidwest .