Matt Wood

Maryam Sule may seem like an unlikely candidate to establish an arboretum in Curtis, Nebraska. She was born in Lagos, Nigeria, a city of 15 million people, and grew up in the suburbs of Denver, Colorado, and Omaha, Nebraska. The engineering major stepped out of her comfort zone and spent the summer of 2023 identifying trees, riding horses, promoting an ag college, and learning about farming and ranching.

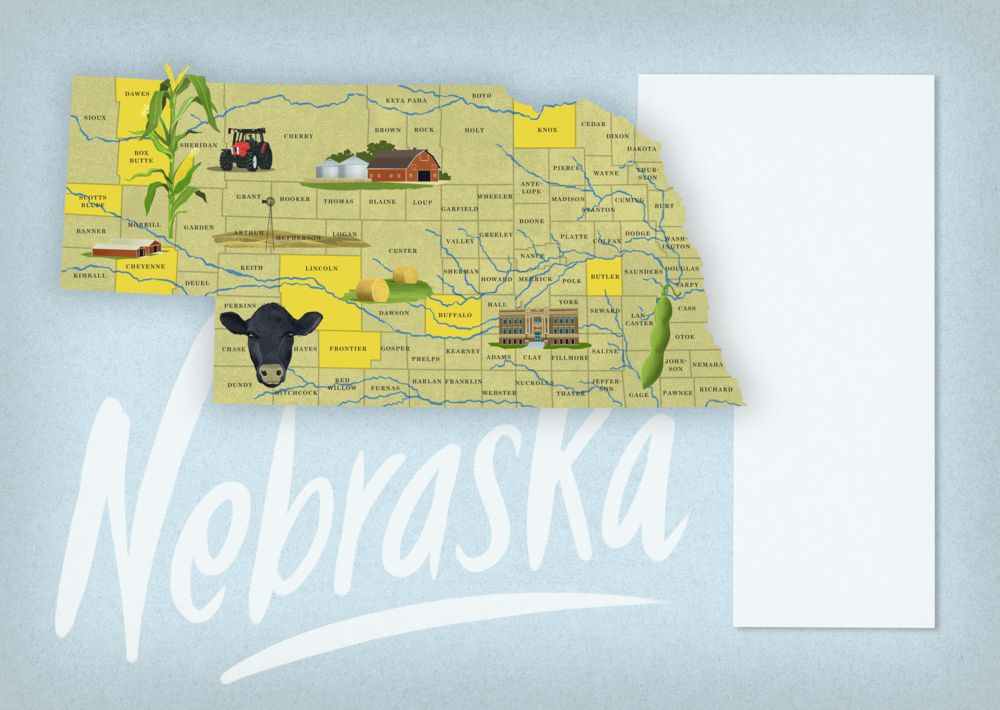

Sule was in Curtis as part of the Rural Fellows program from the University of Nebraska and Rural Prosperity Nebraska, which aims to expose college students to opportunities in the state. In turn, the projects they complete improve the quality of life in those communities, making them more attractive to current and potential residents.

The program places undergraduate and graduate students in Nebraska communities for seven weeks each summer, where they live, work with local leaders, and volunteer. Although most fellows attend one of the University of Nebraska institutions, any college student with any major can apply. The communities provide housing and a $5,000 stipend for each fellow, and the students receive real-world education and get to experience small-town life.

Becoming part of a community

Helen Abdali Soosan Fagan has been managing the Rural Fellows program for six years. “The goal is for the students to grow and see themselves as potential rural community leaders,” she says. “This experience takes what they’re learning in the classroom and brings it to life for them.”

Russell Shaffer is a communications specialist for Rural Prosperity Nebraska. “One of the coolest things about the program,” he says, “is the communities design the projects they want to work on; during the interview process, they select students whose skill set and education best fits the needs of those projects. We had a student map out all the water mains in town. Others created hiking and biking trails, managed social media, built websites, promoted healthy eating, and one even did a geocaching map. It really does run the gamut.”

“The communities are the experts,” Fagan says. “We’re never going to come in and tell them what to do; they know what their needs are. We provide individuals with the passion and skill set to meet those needs.”

Shaffer says the program works because it benefits everyone. “Students are getting real-world experience and a sense of what it’s like to work and live in a community,” he says. “The community gets a breath of fresh air, different perspectives, and the most recent ideas for social media and other projects. Sometimes, it’s easy to fall into patterns, and the rural fellows shake up those patterns.”

Part of Fagan’s role is to attract the best fellows. “There are lots of opportunities for students,” she points out, “so we have to create an experience that meets multiple needs: learning, internship credit, professional experience, and leadership development. We have to be competitive in what we offer.

For some students from New York or Los Angeles or Chicago or Buenos Aires, the idea of going to a rural community may not be as inviting. We want them to realize this is a unique experience.”

Whatever their preconceived notions, many fellows come to see the benefits of rural living. “We did a ‘where are they now’ study of former fellows and found over 57% returned to live or work in a rural community in Nebraska,” Fagan says. “We tell community leaders, ‘This is your chance to woo the students to be potential colleagues.’ ”

Fellows share updates throughout the session and give presentations to program, community, and university leaders during their last weeks. Shaffer helps them with technology and skills for success in this area. “Russell teaches the students how to tell a story — how to take great pictures and capture the essence of the people,” Fagan says. “I think that’s a wonderful skill set for the students to have, even if their life doesn’t take them down a storytelling path.”

Fagan says the benefits of the Rural Fellows program are long lasting. “Community-needs evaluations have been done by fellows that led to millions of dollars in grants or tax benefits for the community,” she says. “Students have gotten early medical or grad school acceptance, and they credit the program.” In many cases, mentoring relationships established extend long past summer.

Giving college graduates a reason to stay or move to rural areas helps reduce brain drain. New data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 American Community Survey shows many rural states continue to experience an outmigration of individuals with bachelor’s or advanced degrees.

When college graduates leave rural America in search of greener pastures, they take more than their talents with them. Local economies suffer because of the lost income, property and sales taxes. When those leaving are parents, school districts lose students and, therefore, funding.

Summer sessions

In 2023, the Rural Fellows program celebrated its 10th anniversary, with 10 communities across the Cornhusker State hosting 19 fellows: 17 from the University of Nebraska and two from universities in Iowa and Colorado. Ten of those from the University of Nebraska were international students.

Sule is a chemical engineering student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and served as a fellow at the Nebraska College of Technical Agriculture (NCTA) in Curtis, a town of about 800 people.

Lisa Foust Prater

“I’d never really experienced rural life before this, and it has been an awesome experience,” she says. “It’s quiet. I knew in a town this size, people would have to be close, but it has been wonderful to see how they care about and support each other.”

Her original project for NCTA was to redevelop relationships with alumni by creating a database, establishing a community on social media, and hosting an alumni event. When the second fellow who was assigned to NCTA had to return to Africa due to a family illness, Sule took on her project as well.

“We asked Maryam if she’d want to work on both of them, and when she agreed, we hired another intern to help,” says Jennifer McConville, associate dean at NCTA. “We talked about a couple of short-term goals, and I never actually intended for her to complete them all this summer, but she pretty much did.”

The second project, reestablishing the school’s arboretum, taught Sule new skills. “I’m not really an outdoor person, but I had to learn to identify trees,” she says. “They all looked the same to me, so I had a little book that I walked around with on campus, and checked the leaves and things to figure out what they were. There were so many opportunities for me to learn more about nature, and the arboretum ended up being my favorite project.”

Sule identified and mapped 200 trees on campus. She also created an audio walking tour, and designed signs that identify the trees: They display QR codes that visitors can scan to link to more information about the type of tree. When Nebraska forestry experts came to identify off-campus trees in Curtis, they confirmed the students identified almost all the trees correctly. “There were about 2% we missed, and they said those were easy to confuse with another tree, so I felt good about that,” Sule says.

McConville says the Rural Fellows program isn’t just about the project itself. “It’s not just coming out here and doing a task,” she says. “It is very inclusive to a number of skill sets, like communication, leadership, inclusivity, and teamwork. The arboretum and the alumni database probably had next to nothing to do with what Maryam actually learned this summer.”

Sule agrees. “Most people think of engineers as nerds on their computers who have no leadership skills, and I could see why,” she says, with a laugh. “But this summer has really helped me get out of my comfort zone and encouraged me to be a leader more, listen to people, communicate with others, and be organized.”

An added bonus is that her tree identification skills are now top-notch. “I was walking to the grocery store the other day and said, ‘Hey, that’s an American linden!’ ” she says.

She also volunteered in the community and found time to have fun, mostly with the ranching interns who were staying at NCTA to take care of livestock over the summer. “The ranch crew is awesome,” she says. “I went horseback riding for the first time, and it was a 10 out of 10 experience. I also got to help out with cattle branding and learned how important that part of agriculture is to Curtis.”

Experiencing rural life has expanded Sule’s ideas when it comes to a career. “I was just a chemical engineering student and really didn’t know what I was going to do with that, but I’m starting to see how maybe I could relate my degree to agriculture,” she says. “I was talking with a farmer about the changing weather patterns and how that affects farming, and it clicked in my head that I want to do something related to climate change.”

One of the best parts of her time in Curtis was experiencing the kindness of its residents. “It has been really nice meeting people who want to take the time to get to know who I am as a person,” she says. “It has been a very heartwarming experience for me, and I have never felt so welcome in my life.”

Spotlight on health

In Nebraska’s Butler County, two rural fellows held workshops focusing on the social determinants of health: the study of how people’s health is affected by where they live, play, and work.

Juliana Monono is an international student from Cameroon in central Africa, earning her Master of Public Health (MPH) in epidemiology from the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Kate Holcomb is an ag education major at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, who grew up on a farm and ranch in Broken Bow, Nebraska.

“This rural health project focuses on how things like your access to education and quality health care, economic stability, and neighborhood come together and impact your health positively or negatively,” Monono says. The fellows held informative workshops and discussions around the county, then noted the issues that were raised and things community members would like to see done differently. “From there, the overarching goal is to create a logic model, so the Extension office will be able to coach communities and take actionable steps to bring change,” she says.

Louise Niemann, the office manager for Butler County Extension, worked closely with the fellows. She says their presentations were held in seven districts in Butler County rather than having everyone come to David City, the county seat. “We wanted to get an overview of the entire county and the different needs in different areas,” she says.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/7019560NRF-davidcitysign-LFP_preview-5852361f71994c2faf6e2dbf29bdd33e.jpg)

Lisa Foust Prater

Because education is one of the social determinants of health, Holcomb could tie the project into her goal of becoming an ag teacher. “In a lot of my education classes, we talk about difficult students, and this makes me more empathetic because there’s a whole long list of things that could be impacting their performance in school,” she says. “I think ag teachers have a really unique opportunity to impact their communities. Being aware of these things will help me be more successful.”

The fellows learned that residents felt a need for local mental and behavioral health practitioners, more jobs for youth, more housing, and additional green spaces. Also, day care was a major issue for many.

Niemann says the community was invested in the project, financially and emotionally. “We have community buy-in because we had to come up with the money,” she says. “It’s a huge investment and says, ‘We believe in this project and these young women, and we’re going to support them.’ ”

Holcomb says, “Everyone has been really receptive to us, and not just a certain group. Different ages, different jobs, and different backgrounds, so that has been fun to see.”

Monono agrees. “It has been amazing going into these different communities,” she says, “and having them be very hands-on: helping us find a good location for the workshop; and helping us invite people, get set up, and engage in the conversations we’re having.”

This project will have an impact far beyond summer. “I’m really excited about the data and information that will help us determine what will make our community better and what we need to address,” Niemann says. “They’ve done all the groundwork for us. They’ve been talking to people I’ve known my whole life, but Juliana and Kate are able to come in with a fresh eye and share what they get from the discussions in an unbiased way.”

Monono says the experience has helped broaden her horizons. “This was my first time in rural Nebraska and my first time working in anything rural health-related, so seeing this perspective has been really helpful,” she says. “It’s a full-circle moment for me in terms of what I’m learning in the classroom and experiencing on the ground.”

The fellows volunteered for 4-H, a community garden, and a food bank, and they served as judges at the county fair. “It was my first county fair,” Monono says. “A lot of firsts for me.”

While Holcomb wasn’t as far from home as Monono, she says, “It’s fun to see how David City is different from my hometown but also how so many things are still the same. I think that’s one of the things that is really sweet about rural Nebraska.”

Niemann says, “When I talked to Juliana and Kate right at the beginning, I said, ‘Our goal is that you are going to love David City so much that you are going to come back and see yourself as part of this community.’ If that doesn’t happen, at the very least, I hope they will remember us, use what they learned here as an example, and come back and visit us.”

Learn More

2023 Rural Fellows Programs

- Box Butte County: Fellows managed social media for the Box Butte Development Corp., sharing posts with marketing tips for local businesses and hosting lunch-and-learn sessions. They also helped businesses with their branding and online presence and created a brand guide for the local school.

- Butler County: The social determinants of health — how the places people live, work, and play affect their health — were discussed in workshops held in Rising City, Dwight, and David City. Fellows gathered community insights and helped brainstorm solutions.

- Dawes County: The fellows designed Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) accommodation guides for the Discover Northwest Nebraska website, so people who are visually impaired or who have other disabilities can better navigate the community. A bicycling guide, itineraries for visitors, and mental health brochures for schools were also created.

- Gibbon (Buffalo County): Fellows planned a Wellness Week, including presentations on Medicaid, food assistance, child care, and immunizations; held a blood drive; and provided free fitness activities. They also promoted the local farmers market and held a workshop on meat factory worker awareness.

- Knox County: Surveys were conducted to identify child care needs, analyze tourism, and examine migration patterns of local high school alumni. Fellows established the first board of directors for the Knox County Arts Council, updated community websites, and identified a list of grants that could improve the quality of life for residents.

- Lincoln County: These fellows developed a marketing plan to attract investors for a new ag education center with an indoor arena at the fairgrounds, which could be used for concerts and other events. They also promoted the county fair and explored rebranding options for the Lincoln County Ag Society.

- Nebraska College of Technical Agriculture, Curtis (Frontier County): This fellow promoted alumni engagement and recruitment through social media. An arboretum was also developed by identifying and researching 200 trees on campus and creating maps, an audio walking tour, and interactive signage.

- North Platte (Lincoln County): Two fellows conducted a housing and community needs assessment by talking with residents, photographing homes, and collecting data on homeownership and value. Another fellow examined more than 70 miles of pavement in the city, evaluating its condition, photographing damage, and analyzing data.

- Sidney (Cheyenne County): Fellows promoted the city’s creative district by making videos highlighting murals, recording the district’s history, and developing a website and social media presence. They worked with the county tourism office to develop a website, marketing material for public buses, and highway signage.

- Scottsbluff (Scotts Bluff County): Projects focused on helping community members become more inclusive. They hosted a Welcoming Communities Conference in cooperation with Empowering Families. Fellows also spent time working with youth in summer camps.

Visit ruralprosperityne.unl.edu to learn more about the Rural Fellows program, which will be paused and evaluated in 2024, with the goal of expanding opportunities for students to serve communities across Nebraska. Contact your local university Extension office to see whether similar programs are available in your state.

Monono says she would encourage any student to apply for a program such as the Rural Fellows. “It provides an environment for you to grow and to recognize what you bring to the table,” she says. “Just understanding that you have something to offer is really empowering and amazing.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/LisaFoustPrater-5d5284849acc417c8678324f9c660161.jpg)