COLUMBIA, Mo. – As dry weather and short pastures abound, Missouri cattle farmers face tough decisions — one way to match cows' needs to available grass is to sell cows.

- READ MORE: 3 tips for drought pasture management

First, give careful thought to which grass eaters go first, says Eric Bailey, University of Missouri Extension beef nutritionist. Under drought stress, identifying those cows becomes urgent.

The first cut is simple, Bailey says. Even the best herds have poor performers that need to be culled. Sell cows that are not pregnant or nursing. There is no feed for freeloaders when forage is short.

"Next, cull lactating cows with bad disposition, bad eyes, bad feet, or bad udders," Bailey says. "Now's time to remove cows with blemishes or poor-doing calves."

Everyone has a cull list, he adds. "But they hesitate to act if a cow has a calf."

Culling helps even in good years because culling poor cows improves overall herd averages.

The goal is to keep best genetics in the herd as long as feasible. Finally, lack of feed or water forces a move.

Downsizing goes beyond simply getting rid of bad cows, Bailey says.

Early weaning and selling calves can cut feed demand. That provides needed cash but can hurt annual income. Another strategy calls for splitting a herd into young and old females.

Sell one of the groups. Two- to 4-year-olds may have superior genetics, but older cows show success in the farm's management.

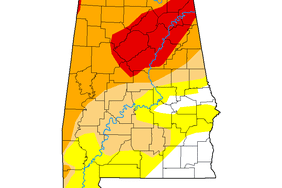

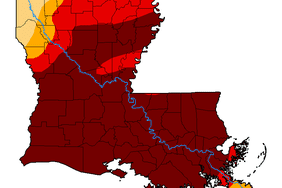

Overall, culling depends on forage outlook for summer, fall, and winter feeding. Level of de-stocking can differ from farm to farm in the same neighborhood.

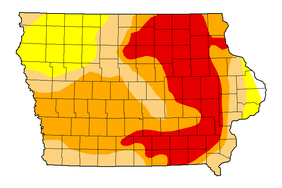

Rainfall patterns vary greatly. Bailey points out that in typical years, two-thirds of forage yield comes in spring growth. One-third comes in fall growth. That's when winter stockpiling should happen.

Missouri producers with cool-season grass always deal with summer slumps. Even if rains return, Bailey cautions, expect below-average fall forage yields. A big long-term problem will be winter feed, Bailey says.

Many farms could be facing severe de-stocking.

"Initially, consider a 25% cut," he says. "If normal rains don't return, consider another 25% later."

Selling calves early in spite of revenue loss may take care of downsizing needs. A 50% cut ahead of fall forage growth may allow stockpiling pastures for winter grazing. That cuts feed buying but that depends on a return of rainfall.

The main advice is to plan downsizing, Bailey says. Management improvements, such as shorter breeding seasons, not year-round calving, can benefit.

For optimists, drought-induced culls can be beneficial as it forces some producers to tough management decisions.

"Producers who last longest in cow-calf businesses are not those who make the most money in good years. They are those who lose the least in bad years," he says.