:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/bradyfahlmanandkellydegelmen-courtesybrady-e21d3a5bdcf44bfb9736d1c9ed443d01.jpeg)

Courtesy of Fahlman Acres

As farmers seek to increase efficiencies or find solutions to labor shortages, their interest in autonomous agriculture increases. Getting there will require more than just buying the latest piece of machinery. Kelly Degelman, a precision ag specialist, is working to put the necessary infrastructure in place at Fahlman Acres in Canada.

Brady Fahlman, a fifth-generation farmer from Holdfast in Saskatchewan, hired Degelman to help prepare his family farm for the future. The pair works with Fahlman’s father on a 13,000-acre operation, where they grow wheat, canola, yellow peas, red lentils, and barley.

The 10-Year Interview

Fahlman had been using a mix of semi-autonomous machinery, but a recent trial with a fully autonomous spreader opened his eyes to the future needs of his farm. In the past, even when working with tech such as GPS and auto steering, getting technical support could be a challenge.

“When the window is open for us to farm, everybody is farming, so everybody’s got problems at the same time,” says Fahlman. “Eventually, we would have to just figure it out — the rain doesn’t care if auto steer works. Having someone on site for support would allow us to have a more effective conversation with our dealer, solve issues quicker, and reduce lost time in the field.”

Fahlman jokes that hiring Degelman was a “10-year interview.” Degelman is relatively new to the agriculture space with a background as an auto body and collision technician. About 13 years ago, he joined an ag equipment dealership, where he started in a support role before being dropped into the world of precision ag.

“Agriculture is interesting because it’s one of the most important puzzles to solve — how do we maximize every acre, waste less, and produce more?” says Degelman. “I’m a self-starter. There was some training through the dealership side, but at that time, there really was no formal education in Canada for precision ag.”

Fahlman and Degelman met when Fahlman’s equipment dealer sent Degelman to work on a blockage monitoring system on one of the farm’s air drills. Degelman continued support on the air drill, and the relationship grew from there.

“With autonomy looking very real, having somebody on the farm to diagnose any tech problems, handle our data, and then take on any projects going forward for us, was absolutely necessary,” says Fahlman.

Building to Autonomy

“Autonomy, like artificial intelligence, is just a bit of a buzzword,” says Degelman.

“I’m looking for something to do little things that the operator doesn’t have to do.”

He describes the journey to autonomy as a pyramid to be optimized. People make up the bottom, followed by machinery, with autonomy at the top of the pyramid.

“Autonomy interests me because it’s the pinnacle of optimization and efficiency, but it can also be the opposite of that if you’re not ready for it,” says Degelman. “Not every farm is ready, but I’ve built a road map in a sense. Start with the basics, make sure everyone understands what we’re doing and why we manage things the way we do. Then you can move forward.”

Now Degelman has his hands involved in most of the farm’s technology and machinery to get these fundamentals in place, at times acting as Fahlman’s adviser.

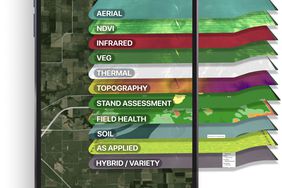

In the winter, he manages the farm’s data — getting equipment ready by creating field names and mapping boundaries — to help build trust with the rest of the employees on the farm.

In the spring, Degelman does whatever needs to be done in the shop or field. He spends time in the combine, tractor, and sprayer so he can learn more about potential efficiencies on the equipment and how to pass that information along.

“I’m like the coach — once people understand why you’re doing something, they’re more likely to cooperate,” says Degelman. “Manufacturers want flashy technology, but they can’t forget about people. It’s the people that are still going to drive this. We’re so far away from machinery completely operating on its own.”

He hopes to see more people — especially those like him without a background in agriculture — get involved in precision ag.

“I didn’t think this was an actual career category, but maybe we are the blueprint,” says Degelman. “Autonomy is there to solve the labor challenge, but that will still be there because somebody still needs to, in a sense, operate the autonomous equipment.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/_D3_6951-2b36bbe5727444fb9b3b968da4e62f78.jpg)